Justice Manmohan Singh of the Delhi High Court has remarked in a judgment, “The world is a global village.” This sentiment captures the essence of our interconnected era, where globalization and interconnected markets continually redefine our world. Today, the judgments handed down in courtrooms across the globe can have far-reaching consequences, and the ripples of these legal decisions, especially in the realm of trademarks, extend far beyond their local jurisdictions, influencing economies and industries worldwide.

Welcome to “A View from Afar,” a series dedicated to examining international judgments and their far-reaching impacts. Through this series, we aim to bridge the gap between diverse legal systems and their global repercussions, offering you a panoramic view of the intricate interplay between law and commerce.

We will delve into landmark rulings from various corners of the world, unpacking the legal reasoning behind such decisions and scrutinizing their practical implications. Each article will provide a thorough analysis, shedding light on how these judgments affect not only the parties directly involved but also affect the regulatory frameworks, corporate strategies, and market dynamics on a global scale.

In whichever jurisdiction a judgment is delivered, we will share our views on its profound impact in other jurisdictions navigating through the labyrinth of international jurisprudence.

Join us in this further instalment of “A View from Afar” as we delve into the nuances of a recent case involving the tension between creative expression and public morality. This case, which took nearly six years to resolve, underscores the delicate balance trademark law must strike between safeguarding creative branding and respecting societal norms.

In the creation of Valley of Mother of God Gin, the founders of Foxglove Spirits, Malcolm Roberts and Shelly Perry, were inspired by the serene and verdant landscapes surrounding their Ontario farm. Their intention was to capture this essence in a brand that represented their dedication to producing exceptional gin. However, what began as a simple trademark application to protect their brand quickly transformed into a protracted legal battle spanning six years. The case demonstrates the complexities of trademark law, particularly when a brand name intersects with religious connotations and public sensitivities.

The Trademark Dispute

In 2018, Foxglove Spirits applied to the Canadian Intellectual Property Office (CIPO) to register the trademark Valley of Mother of God for their range of alcoholic beverages. The name, drawn from the nearby landscape where the company sourced its ingredients, was meant to evoke imagery of natural beauty and purity. Malcolm Roberts, an advertising expert and co-founder, aimed to create a brand name that would leave a lasting impression. However, their application met resistance due to certain provisions of Canadian trademark law.

CIPO initially rejected the application on the grounds that the trademark could be considered “scandalous, obscene, or immoral” under Section 9(1)(j) of the Trademarks Act of Canada. This decision left Foxglove in a difficult position, as the rejection came without a clear explanation or supporting evidence. The company faced the challenge of responding to an ambiguous ruling, a common frustration for applicants seeking to protect unique or potentially contentious trademarks.

The Legal Framework: A Comparative Perspective

The core issue in this case was CIPO’s application of the “scandalous, obscene, or immoral” standard. These terms are not clearly defined in Canadian trademark law, leaving much room for interpretation. Foxglove’s case highlights the subjective nature of such assessments, which can vary based on societal norms and values at the time of the application.

In Canada, religious references in trademarks have often been viewed through a conservative lens. For example, in the Hallelujah case, the use of the word in relation to women’s clothing was deemed inappropriate due to its overwhelming religious significance. The refusal was based on the “overwhelming religious significance” of the word, which, the Court reasoned, would offend the accepted mores of the time (being the mid-1970s). This case still stands for the proposition that Canadian trademarks containing any religious references are generally considered inappropriate for registration.

This conservative stance is not unique to Canada; in the United Kingdom, the term OOMPHIES was denied registration in 1946 for being considered slang for sex appeal, reflecting the cultural sensitivities of that era. In the case of La Marquise Footwear Inc. Re. (1946), 64 R.P.C. 27, In The High Court of Justice-Chancery Division, Justice Evershed had observed,

…it is the duty of the Registrar (and it is my hope that he will always fearlessly exercise it) to consider not merely the general taste of the time, but also the susceptibilities of persons, by no means few in number, who still may be regarded as old fashioned and, if he is of the opinion that the feelings or susceptibilities of such people will be offended, he will properly consider refusal of the registration.

In contrast, other jurisdictions have evolved in their approach to potentially offensive trademarks. In Drolet v Stiftung Gralsbotschaft, the disputed trademarks included religious words and symbols, such as the menorah. This time the Court found that the trademarks were not scandalous, obscene, or immoral, even if they might offend certain groups.

In Constantin Film Produktion GmbH v European Union Intellectual Property Office (EUIPO), the European Court of Justice clarified that “accepted principles of morality” should be interpreted in context, reflecting a society’s fundamental moral values and standards, which are subject to change. The assessment of a trademark’s moral acceptability must consider the social context, including cultural, religious, and philosophical diversity, and should be based on the perspective of reasonable persons with average sensitivity and tolerance.

The United States has also taken significant steps to protect freedom of expression, as seen in Iancu v Brunetti 139 S. Ct. 2294 (2019), overturned the past prohibition against registering trademarks, where the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that prohibiting the registration of “immoral or scandalous” trademarks violated the First Amendment. This decision came after the attempted registration of the brand FUCT, a controversial acronym (“Friends U Can’t Trust”) which was deemed “immoral or scandalous.” In this case, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that this prohibition was unconstitutional for violating free speech, being overly broad and covered many ideas far beyond the initial issue of $%%#@ words. The Court held that this provision in the law violated the rights of applicants to free expression since, the mark FCUK (for “French Connection United Kingdom”), has long been accepted in Canada and the US

Similarly, In Joseph Matal v. Simon Tam, the U.S. Supreme Court observed that a refusal to register a trademark on grounds of offensiveness violated the right to free speech and consequently ruled in favor of a band named The Slants, holding that offensive trademarks were still entitled to protection under the law.

While these cases reflect the protection of free speech, the application of similar standards in Canada remains cautious.

The Response to CIPO’s Objections

Undeterred by CIPO’s refusal, Foxglove mounted a well-prepared legal response. Their argument rested on the principle that for a trademark to be considered scandalous, obscene, or immoral, it must offend a “not insignificant segment” of the public. The Trademarks Examination Manual provides some guidance, but its definitions are often broad and open to interpretation:

- Scandalous: A word or design is considered scandalous if it is offensive to public or individual propriety or morality or is a slur on nationality and generally regarded as offensive. It is generally defined as causing widespread outrage or indignation.

- Obscene: A word is considered obscene if it violates accepted language inhibitions or is regarded as taboo in polite usage. It is generally defined as offensive or disgusting by accepted standards of morality or decency or offensive to the senses.

- Immoral: A word or design is considered immoral if it conflicts with generally or traditionally held moral principles and is defined as not conforming to accepted moral standards.

Considering these criteria, the applicant argued that its trademark was neither obscene nor immoral, leaving only the question of whether it could be deemed scandalous. It was contended that the trademark would not offend the general public’s feelings or sensibilities, and merely offending certain individuals does not meet the required threshold for being deemed scandalous.

However, the Canadian Intellectual Property Office (CIPO) was unconvinced and issued a second refusal, denying the application once again. The Examining officer, while offering no substantial evidence, relied on the Oxford Dictionary. CIPO cited the dictionary definition of “Mother of God” in the context of the Christian Church, which refers to the Virgin Mary as “the mother of the divine Christ.” The Examiner argued that for “the average Canadian with average education in English and/or French,” the first impression of the trademark would be considered scandalous, obscene, or immoral.

In response, Foxglove Spirits presented evidence that their brand had been extensively marketed and distributed, particularly through the Liquor Control Board of Ontario (LCBO), without receiving a single complaint. Additionally, they placed on record, affidavits from religious leaders who found the trademark to be non-offensive, further demonstrating that the public’s perception was not aligned with CIPO’s objections.

A Shifting Legal Landscape

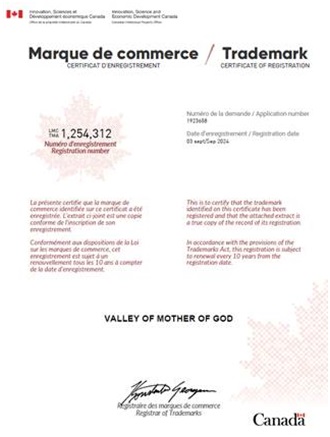

Although the application for Valley of Mother of God was eventually approved in September 2024, the case underscores the need for a more coherent and predictable standard in assessing potentially scandalous or offensive trademarks. As public morality is not static and continues to evolve, so too must the laws that govern these issues.

*We do not claim any copyright in the above image. The same has been reproduced for academic and representational purposes only.

In jurisdictions like India, the law similarly prohibits the registration of marks that contain scandalous or obscene matter. Section 9 of the Indian Trademarks Act, 1999 mirrors the Canadian provisions, providing absolute grounds for refusal if a trademark is likely to hurt religious susceptibilities or conflict with public morality. Section 9 of the Trademarks Act, 1999 (hereinafter referred to as “the Act”) provides absolute grounds for refusal of a trademark registration. Among the grounds listed, Section 9(2)(c) specifically bars the registration of trademarks that are deemed to contain scandalous or obscene matter. This provision reflects a broader public policy consideration—protecting societal norms and moral values. However, defining what constitutes “scandalous” or “obscene” in trademark law remains a complex issue, open to interpretation by courts and examiners alike.

Section 9(2)(c): Obscenity and Scandalous Marks

Section 9(2)(c) of the Trade Mark Act, 1999 prohibits the registration of marks that indicate or contain matter likely to hurt religious susceptibilities; or scandalous or obscene material, making it an absolute ground for refusal. However, what qualifies as scandalous or obscene is not clearly defined in the Act. Instead, the determination is left to the facts and circumstances of each case, relying on societal norms, which can shift over time.

According to the Draft Manual for Trademark Practice and Procedure, 2015 (hereinafter referred to as “the Manual”), the test for obscenity must be more than subjective distaste; it must involve material that causes public outrage and undermines religious, social, or family values. The outrage should arise among an identifiable section of the public. The Manual also highlights that examiners must be objective—neither overly conservative nor trendsetting—when applying this provision.

Judicial Interpretations in India

Indian Courts have explored the concepts of obscenity and scandalous material in several notable cases, with mixed outcomes, depending on the legal standards applied.

- The Hicklin Test: Ranjit D. Udheshi v. State of Maharashtrain the landmark case of Ranjit D. Udheshi v. State of Maharashtra, the scope of obscenity was interpreted in respect of the publication and sale of un-expunged copies of DH Lawrence’s Lady Chatterley’s Lover. The novel spoke about the extramarital relationship between an aristocratic woman and her gamekeeper. The Supreme Court of India adopted the Hicklin test from R v. Hicklin. According to this test, any material that tends to “deprave and corrupt” minds vulnerable to such influences can be considered obscene, even if only a portion of the material meets this criterion. However, this test was later criticized for being overly broad and for failing to consider the artistic or literary merit of the material in question.

- The Community Standard Test: Aveer Sarkar v. State of West Bengal in contrast, the Hon’ble Supreme Court of India, in Aveer Sarkar v. State of West Bengal, adopted the community standard test, emphasizing the impact on the public as a whole. In this case, which involved a photograph of a naked woman, the Court ruled that nudity alone does not constitute obscenity. The photograph, which critiqued racism, was not intended to excite sexual desire and thus was not deemed obscene.Similarly, in the controversial case involving artist MaqboolFida Husain’s painting of a nude woman titled “Bharat Mata,” the Courts further refined the test for obscenity. The Court held that nudity does not inherently make a work obscene; it must be shown to arouse sexual desires. Husain’s painting, created for a charity event, was not seen as offensive or obscene under this standard.

- An Objective Standard: S. Rangarajan v. Jagjivan Ram in the case of S. Rangarajan v. Jagjivan Ram, the producer of the film Ore OruGramathile applied for an exhibition certificate. The film addressed the theme that reservation policies should be based on economic conditions rather than the caste system. The film did not raise any issues related to caste considerations, nor did it touch upon matters concerning the sovereignty, integrity, or national security of India. Initially, the Examining Committee refused to grant the exhibition certificate.Following the release of the film, a writ petition was filed in the Madras High Court, arguing that the film irresponsibly portrayed the government’s reservation policy. The Division Bench of the High Court revoked the exhibition certificate, citing concerns raised by a minority section of the public. Consequently, the producer appealed the decision before the Hon’ble Supreme Court of India.

The Supreme Court clarified that the perspective of an “ordinary person of common sense and prudence” should be applied, rather than that of a hypersensitive individual. This standard offers a balanced approach in determining what might be considered scandalous or obscene. (add facts)

Upon a perusal of the records of the Trade Marks Registry, several instances emerge where the Ld. Registrar has refused trademark applications on the grounds of containing obscene or scandalous matter.

A notable case involves Digital Radio (Delhi) Broadcasting Limited, which applied for the trademark registration of the mark “SANSKARI SEX” (Apl no. 4344760) (translated as “Cultured Sex”). The proprietor filed two applications—one for a word mark and another for a device mark. However, the Registrar refused the application and held that “The applicant submitted that the applied mark is coined, innovative, unique combination and distinctive. It does not designate any characteristics of the applied services. Therefore, prayed for acceptance of the mark. However, the applied mark consists of obscene or scandalous matters which is prohibited u/s 9(2)(c) of the Trade Marks Act,1999. Hence, refused.”

At the Chennai Trade Marks Registry, an objection was raised against the registration of the mark “BOOBS & BUDS,” (Apl no. 5335706) citing it as containing scandalous or obscene content. Similarly, in 2019, an applicant sought registration for the mark “NANGA PUNGA” (translated as “Nude/Naked”), however the examination report issued in the instant matter, objected to the mark under Section 9(2)(c) of the Trade Marks Act, 1999.

In April 2019, an applicant applied for the registration of three marks, ‘FUCK CHARDONNAY,’ ‘FUCK MERLOT’ and ‘FUCK CABERNET,’ in respect of alcoholic preparations. All the three applications were objected for containing scandalous or obscene content.

Additionally, there have been several notable cases where trademarks were refused under this provision due to their offensive or objectionable nature:

- Amritpal Singh v. Lal BabuPriyadarshini (2005 (30) PTC 94 (IPAB))

In this case, the applicant applied for the registration of the trademark “RAMAYAN” for incense sticks.The mark was opposedon the groundsthat “RAMAYAN” is the name of a sacred Hindu epic, and using it as a commercial trademark would offend the religious sentiments of Hindus. The Intellectual Property Appellate Board (IPAB) refused registration of the mark under Section 9(2)(c) of the Trade Marks Act, 1999, and held that the use of the word “RAMAYAN,” a revered religious text, for commercial purposes could hurt the religious sentiments of Hindus. The decision emphasized that religious terms should not be monopolized for business use, as this could cause offense to the public and violate public policy.

- Khoday Distilleries Ltd. V. Registrar of Trade Marks (1995)

The appellant sought to register the mark “RAMBO”, which the Trademark Registry refused on the grounds that the mark was scandalous and likely to offend religious sentiments, as “Rambo” could be associated with the Hindu god “Ram.” The registration was denied, emphasizing that trademarks which could offend religious sentiments would not be allowed under Section 9(2)(c).

- Application for the Trademark ‘ROZBAL LINE’

The book title “Rozabal Line” by AshwinSanghi was submitted for trademark registration. The term “Rozabal” refers to a shrine in Kashmir, believed by some to house the tomb of Jesus Christ. The application was objected to under Section 9(2)(c), as it was deemed to hurt religious sentiments by linking the term to controversial religious beliefs. The trademark was refused on the grounds of being scandalous or likely to hurt religious sentiments.

- Application for the Trademark ‘BOSOM’

An application was filed for the mark ‘BOSOM’, associated with a brand of lingerie. The Trade Marks Registry refused to grant protection to the mark under Section 9(2)(c), as it could be viewed as referring explicitly to a body part in a vulgar manner.

Contemporary Examples:

A modern instance of public sensitivity arose in the Myntra logo case, where a complaint was filed claiming that the logo (a stylized ‘M’) was offensive to women. In response, Myntra altered its logo, although many viewed the complaint as an overreaction. This example underscores the tension between hypersensitive interpretations of obscenity and the objective standard applied by Courts.

Similarly, the global brand “FCUK” (French Connection United Kingdom) faced several challenges in India as the term was argued to be phonetically similar to a vulgar swearword, potentially making it scandalous or obscene under Section 9(2)(c). While the mark was permitted for certain categories, it faced objection and was refused in cases where it was deemed offensive or scandalous in connection with specific products or contexts.

The Need for Clearer Standards

In India, Courts have consistently applied the community standard test to ascertain obscenity in trademarks. However, as public morality varies widely across India’s diverse cultures and regions, there is no clear benchmark for what constitutes obscene or scandalous material. The ambiguity in determining obscenity, combined with the subjectivity of morality, raises concerns about the arbitrary rejection of trademark applications. It is argued that a more predictable and coherent standard should be developed, one that accommodates free speech while respecting public sensitivities.While the objective standard articulated in S. Rangarajan v. Jagjivan Ram remains the most reliable guidepost, it will be necessary for lawmakers and the judiciary to refine and clarify the obscenity clause under Section 9 to prevent inconsistent application and ensure fairness in trademark registration.Ultimately, the aim should be to strike a balance between protecting public morality and upholding the rights of trademark owners, ensuring that decisions are not driven by the whims of a vocal minority but by a robust, predictable legal framework.