The Role of Humans in AI-Generated Inventions: Lessons from the DABUS Patent Case

Justice Manmohan Singh of the Delhi High Court has remarked in a judgment, “The world is a global village.” This sentiment captures the essence of our interconnected era, where globalization and interconnected markets continually redefine our world. Today, the judgments handed down in courtrooms across the globe can have far-reaching consequences and the ripples of these legal decisions extend far beyond their local jurisdictions, influencing economies and industries worldwide.

Welcome to “A View from Afar,” a series dedicated to examining international judgments and their far-reaching impacts. Through this series, we aim to bridge the gap between diverse legal systems and their global repercussions, offering you a panoramic view of the intricate interplay between law and commerce.

We will delve into landmark rulings from various corners of the world, unpacking the legal reasoning behind such decisions and scrutinizing their practical implications. Each article will provide a thorough analysis, shedding light on how these judgments affect not only the parties directly involved but also affect the regulatory frameworks, corporate strategies, and market dynamics on a global scale.

Whether it is a judgment delivered in the United States or the European Union, we will share our views on its profound impact in other jurisdictions navigating through the labyrinth of international jurisprudence.

Join us in this further instalment of “A View from Afar” as we delve into the nuances of the landmark decision, passed by Germany’s highest civil court, the Bundesgerichtshof, that elucidates several pivotal principles concerning AI-generated inventions and their eligibility for patent protection. The key takeaways are as follows:

- The decision underscores that even in instances where an invention is generated by artificial intelligence, there is invariably a human presence that exerts a decisive influence on the invention’s creation. This human element is essential and irreplaceable in the process.

- The ruling makes it clear that the type of influence exerted by the human is of no consequence. Whether the contribution is inventive or non-inventive, what matters is the existence of the human involvement.

- The decision recognises that the human being who has exerted his or her influence must be identified and formally designated as the inventor. This requirement ensures that the legal framework for intellectual property which recognizes that human agency in the creation of an invention even when facilitated by AI is acknowledged.

- The decision affirms that inventions generated with the assistance of AI can indeed qualify for patent protection, provided that a human contributor is identified as the inventor however small his or her role in creating the invention may be. This aspect of the ruling is particularly significant as it paves the way for recognizing and protecting AI-facilitated inventions under existing patent laws.

This decision resolves a split between German federal appellate courts, which had previously issued conflicting rulings on the matter and stems from the case involving a lunchbox design created by an AI system known as DABUS (Device for Autonomous Bootstrapping of Unified Sentience), invented by Stephen Thaler. The applicant filed a patent application October 17, 2019. Claim 1 of the application was formulated as follows:

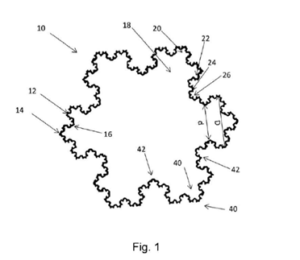

A food or beverage container comprising:

- a wall defining an inner chamber of the container, the wall having inner and outer surfaces and being of substantially uniform thickness;

- wherein the wall has a fractal profile with corresponding convex and concave fractal elements on corresponding elements of the inner and outer surfaces; and whereby the convex and concave fractal elements form depressions and elevations in the profile of the wall.

An embodiment example was depicted in axial cross-section in Figure 1.

Source – Judgement

The inventor designation on the official form indicated that the invention was independently created by the artificial intelligence system, DABUS. The patent office rejected the application after prior notice, on the grounds that only a natural person could be named as the inventor. This led the applicant to file an appeal against the decision.

During the appeal proceedings, the applicant primarily requested that the aforementioned inventor designation be allowed with the addition “c/o Stephen L. Thaler, PhD.” However, the patent office rejected the applicant’s auxiliary requests. In his third auxiliary request, the applicant sought the following amendment: “Stephen L. Thaler, PhD, which prompted the artificial intelligence DABUS to generate the invention.” The Patent Court set aside the decision of the Patent Office and referred the case back to the Patent Office, stipulating that the designation of the inventor pursuant to auxiliary request 3 was to be recognized as having been filed in due time and form.

With its appeal on points of law admitted by the Patent Court, the President of the Patent Office sought to have the decision set aside insofar as the granting of the appeal. The applicant opposed this and pursued his claims rejected by the Patent Court with an interlocutory appeal. The President opposed this appeal, justifying its decision by stating that, according to the current legal situation, only natural persons, and not machines, may be named as inventors. The decision to recognize the inventor’s status with the right to be named (“inventor’s honour”) implies that, under German law, an artificial intelligence cannot be named as an inventor or co-inventor.

Subsequently, this case was pursued by the Artificial Inventor Project, which initiated a series of pro bono legal test cases seeking intellectual property rights for AI-generated output in the absence of a traditional human inventor or author in various jurisdictions, including Germany.

The Bundesgerichtshof(Germany’s highest civil court)held that an AI-generated invention is protectable under German patent law. The Court emphasized that the involvement of AI in generating the invention does not justify the rejection of the patent application. According to the Court, as long as a natural person is named as the inventor, the invention can be patented thus ensuring that, such inventions are eligible for patent protection in Germany. This decision stands in contrast to jurisdictions like the United States and the United Kingdom, where AI-generated inventions are not considered patentable unless a natural person makes a substantial contribution to the invention.

This ruling has significant implications for the international debate on the ownership and protection of AI-generated inventions. Different jurisdictions have varying stances on AI-generated inventions. South Africa made headlines in 2021 by issuing the first patent with AI listed as the inventor, followed by an initial ruling in Australia that allowed AI to be listed as an inventor. However, the Australian ruling was later overturned, and the High Court declined to review the case. In contrast, the European Patent Office (EPO), the United Kingdom, the United States, and Australia have consistently rejected patent applications listing AI as the inventor.

This decision is a pivotal development in the ongoing international debate regarding the ownership and protection of AI-generated inventions and suggests an alternative solution to this issue. While it brings clarity within Germany, it adds complexity to the global discourse on intellectual property rights concerning AI-generated outputs. Additionally, the ruling does not resolve questions about AI inputs, such as the use of existing codes by AI systems like GitHub Copilot, which recently faced legal scrutiny in the United States.

The German Federal Patent Court’s earlier decision, which the recent ruling has now overturned, stated that AI systems could not be designated as inventors. The Court emphasized the concept of the “inventor’s honor” i.e. a public recognition of one’s inventorship, which it argued did not apply to AI systems. However, the Federal Court of Justice has now clarified that while an AI system cannot be the inventor, the use of AI in the inventive process does not invalidate a patent application as long as a natural person is named as an inventor.

This decision has significant implications for the future of AI in innovation. It encourages transparency regarding the involvement of AI in the inventive process and ensures that AI-generated outputs are protectable under patent law. The ruling is particularly crucial for industries relying on AI for developing new technologies, drugs, and industrial components.Notably, the US Congress is currently contemplating changes to its patent laws to keep pace with advancements in AI.

This case and the facts surrounding it, prompted me to analyse the implications of the same with respect to the Indian patent landscape and consider the key takeaways &reforms necessary in the Indian patent laws to accommodate the realities of AI-generated inventions.

In India, the patent landscape is governed by the Patents Act, 1970, which stipulates that an inventor must be a “true and first inventor” and a natural person. This poses a challenge when considering the patentability of AI-generated inventions, as current Indian laws does not explicitly recognize AI as an inventor. However, the German ruling can serve as a profound and precedent-setting stance on the intersection of artificial intelligence and intellectual property law for Indian policymakers in re-evaluating and potentially updating the existing patent laws to address the emergence of AI-generated inventions.

The crux of the matter is that for any AI-generated invention, there must be a human exerting a decisive influence on its creation. This influence is a requisite, irrespective of its nature, which means it need not be inventive or involve creative ingenuity. Furthermore, irrespective of the human contribution being minimal or procedural; what matters is the presence of a human element and that only with the identification and designation of a human as the inventor can an AI-generated invention qualify for patent protection.

This is because a human is essentially the one who provides the necessary guidance to the AI system through prompts, enabling it to produce the desired output. Furthermore, it is the human who refines and improves upon the AI-generated output, ultimately inventing the final invention, including drafting of the specification.

The ruling in this judgement has highlighted the traditional view that patents are legal instruments designed to recognize and reward human ingenuity. By insisting on a human inventor, the Bundesgerichtshof has ensured that the legal framework remains anchored to its foundational principles, despite the advent of advanced technologies capable of autonomous invention. This decision is poised to have far-reaching implications, as it balances the need to embrace technological advancements with the imperative to uphold the human-centric nature of intellectual property law.